The commercial marketplace of Madhu Vihar isn’t exactly a typical location for the headquarters of a successful e-commerce venture. And when you meet 31-year-old Dinesh Agarwal, he turns out to be the exact antithesis of the swish e-entrepreneur you’d expect him to be.

The commercial marketplace of Madhu Vihar isn’t exactly a typical location for the headquarters of a successful e-commerce venture. And when you meet 31-year-old Dinesh Agarwal, he turns out to be the exact antithesis of the swish e-entrepreneur you’d expect him to be.

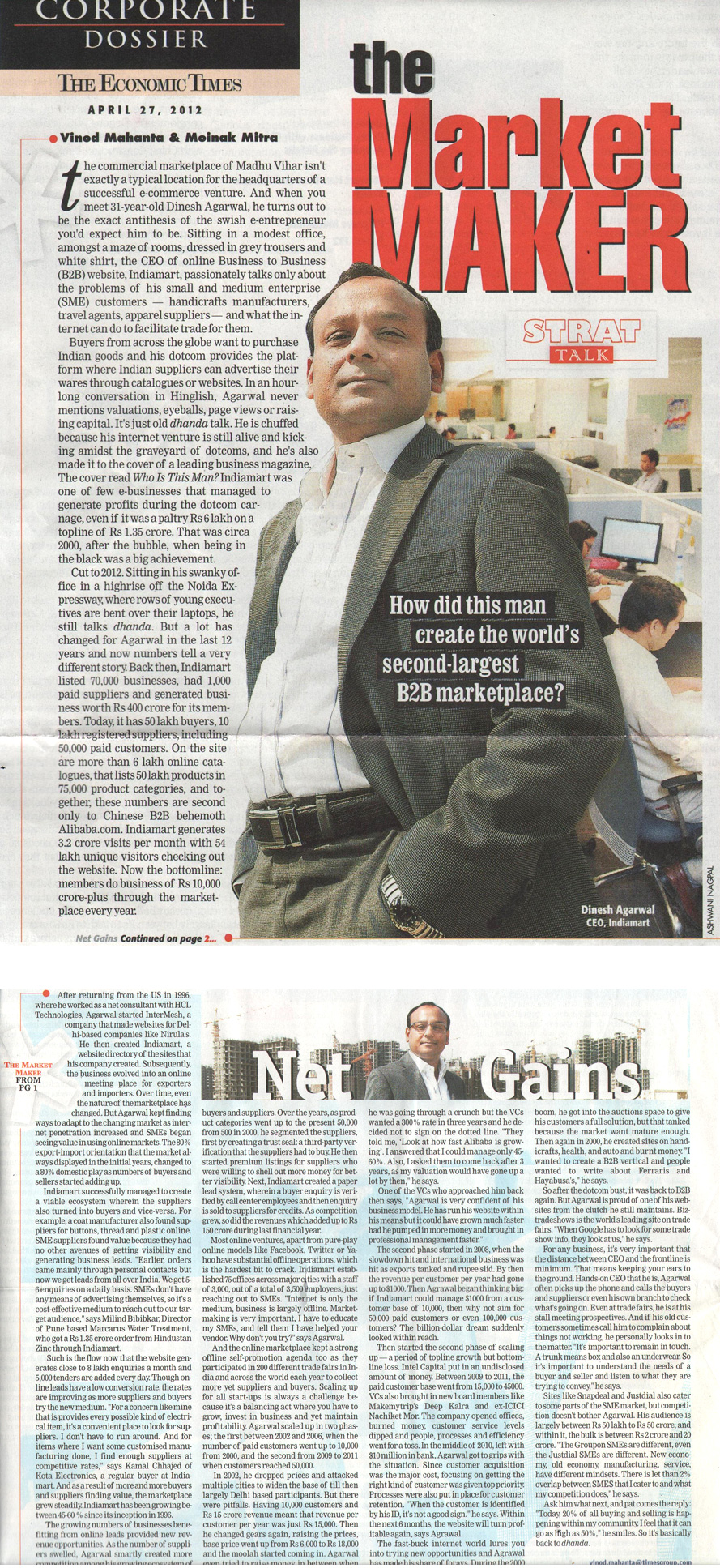

Sitting in a modest office, amongst a maze of rooms, dressed in grey trousers and white shirt, the CEO of online Business to Business (B2B) website, Indiamart, passionately talks only about the problems of his small and medium enterprise (SME) customers – handicrafts manufacturers, travel agents, apparel suppliers – and what the internet can do to facilitate trade for them.

Buyers from across the globe want to purchase Indian goods and his dotcom provides the platform where Indian suppliers can advertise their wares through catalogues or websites. In an hourlong conversation in Hinglish, Agarwal never mentions valuations, eyeballs, page views or raising capital. It’s just old dhanda talk. He is chuffed because his internet venture is still alive and kicking amidst the graveyard of dotcoms, and he’s also made it to the cover of a leading business magazine.

The cover read Who Is This Man? Indiamart was one of few e-businesses that managed to generate profits during the dotcom carnage, even if it was a paltry Rs 6 lakh on a topline of Rs 1.35 crore. That was circa 2000, after the bubble, when being in the black was a big achievement. Cut to 2012. Sitting in his swanky office in a highrise off the Noida Expressway, where rows of young executives are bent over their laptops, he still talks dhanda.

But a lot has changed for Agarwal in the last 12 years and now numbers tell a very different story. Back then, Indiamart listed 70,000 businesses, had 1,000 paid suppliers and generated business worth Rs 400 crore for its members. Today, it has 50 lakh buyers, 10 lakh registered suppliers, including 50,000 paid customers.

On the site are more than 6 lakh online catalogues, that lists 50 lakh products in 75,000 product categories, and together, these numbers are second only to Chinese B2B behemoth Alibaba.com. Indiamart generates 3.2 crore visits per month with 54 lakh unique visitors checking out the website. Now the bottomline: members do business of Rs 10,000 crore-plus through the marketplace every year.

After returning from the US in 1996, where he worked as a net consultant with HCL Technologies, Agarwal started InterMesh, a company that made websites for Delhi-based companies like Nirula’s. He then created Indiamart, a website directory of the sites that his company created. Subsequently, the business evolved into an online meeting place for exporters and importers. Over time, even the nature of the marketplace has changed. But Agarwal kept finding ways to adapt to the changing market as internet penetration increased and SMEs began seeing value in using online markets.

The 80% export-import orientation that the market always displayed in the initial years, changed to a 80% domestic play as numbers of buyers and sellers started adding up.

Indiamart successfully managed to create a viable ecosystem wherein the suppliers also turned into buyers and vice-versa. For example, a coat manufacturer also found suppliers for buttons, thread and plastic online. SME suppliers found value because they had no other avenues of getting visibility and generating business leads. “Earlier, orders came mainly through personal contacts but now we get leads from all over India. We get 5-6 enquiries on a daily basis. SMEs don’t have any means of advertising themselves, so it’s a costeffective medium to reach out to our target audience,” says Milind Bibibkar, Director of Pune based Marcarus Water Treatment, who got a Rs 1.35 crore order from Hindustan Zinc through Indiamart.

Such is the flow now that the website generates close to 8 lakh enquiries a month and 5,000 tenders are added every day. Though online leads have a low conversion rate, the rates are improving as more suppliers and buyers try the new medium. “For a concern like mine that is provides every possible kind of electrical item, it’s a convenient place to look for suppliers. I don’t have to run around. And for items where I want some customised manufacturing done, I find enough suppliers at competitive rates,” says Kamal Chhajed of Kota Electronics, a regular buyer at Indiamart. And as a result of more and more buyers and suppliers finding value, the marketplace grew steadily. Indiamart has been growing between 45-60 % since its inception in 1996.

The growing numbers of businesses benefitting from online leads provided new revenue opportunities. As the number of suppliers swelled, Agarwal smartly created more competition among his growing ecosystem of buyers and suppliers. Over the years, as product categories went up to the present 50,000 from 500 in 2000, he segmented the suppliers, first by creating a trust seal: a third-party verification that the suppliers had to buy. He then started premium listings for suppliers who were willing to shell out more money for better visibility. Next, Indiamart created a paper lead system, wherein a buyer enquiry is verified by call center employees and then enquiry is sold to suppliers for credits. As competition grew, so did the revenues which added up to Rs 150 crore during last financial year.

Most online ventures, apart from pure-play online models like Facebook, Twitter or Yahoo have substantial offline operations, which is the hardest bit to crack. Indiamart established 75 offices across major cities with a staff of 3,000, out of a total of 3,500 employees, just reaching out to SMEs. “Internet is only the medium, business is largely offline. Marketmaking is very important, I have to educate my SMEs, and tell them I have helped your vendor. Why don’t you try?” says Agarwal.

And the online marketplace kept a strong offline self-promotion agenda too as they participated in 200 different trade fairs in India and across the world each year to collect more yet suppliers and buyers. Scaling up for all start-ups is always a challenge because it’s a balancing act where you have to grow, invest in business and yet maintain profitability. Agarwal scaled up in two phases; the first between 2002 and 2006, when the number of paid customers went up to 10,000 from 2000, and the second from 2009 to 2011 when customers reached 50,000.

In 2002, he dropped prices and attacked multiple cities to widen the base of till then largely Delhi based participants. But there were pitfalls. Having 10,000 customers and Rs 15 crore revenue meant that revenue per customer per year was just Rs 15,000. Then he changed gears again, raising the prices, base price went up from Rs 6,000 to Rs 18,000 and the moolah started coming in. Agarwal even tried to raise money in between when he was going through a crunch but the VCs wanted a 300% rate in three years and he decided not to sign on the dotted line. “They told me, ‘Look at how fast Alibaba is growing’. I answered that I could manage only 45-60%. Also, I asked them to come back after 3 years, as my valuation would have gone up a lot by then,” he says.

One of the VCs who approached him back then says, “Agarwal is very confident of his business model. He has run his website within his means but it could have grown much faster had he pumped in more money and brought in professional management faster.”

The second phase started in 2008, when the slowdown hit and international business was hit as exports tanked and rupee slid. By then the revenue per customer per year had gone up to $1000. Then Agrawal began thinking big: if Indiamart could manage $1000 from a customer base of 10,000, then why not aim for 50,000 paid customers or even 100,000 customers? The billion-dollar dream suddenly looked within reach.

Then started the second phase of scaling up – a period of topline growth but bottomline loss. Intel Capital put in an undisclosed amount of money. “Our thesis at the time of investment was that it was a good and interesting space domesticaly and globally. And Indiamart was growing consistently and poised for dominence,” says ex VC Sarayu Srinivasan who led the investment for Intel Capital. Between 2009 to 2011, the paid customer base went from 15,000 to 45000. VCs also brought in new board members like Makemytrip’s Deep Kalra and ex-ICICI Nachiket Mor. The company opened offices, burned money, customer service levels dipped and people, processes and efficiency went for a toss. In the middle of 2010, left with $10 million in bank, Agarwal got to grips with the situation. Since customer acquisition was the major cost, focusing on getting the right kind of customer was given top priority. Processes were also put in place for customer retention. “When the customer is identified by his ID, it’s not a good sign.” he says. Within the next 6 months, the website will turn profitable again, says Agrawal.

The fast-buck internet world lures you into trying new opportunities and Agrawal has made his share of forays. During the 2000 boom, he got into the auctions space to give his customers a full solution, but that tanked because the market want mature enough. Then again in 2000, he created sites on handicrafts, health, and auto and burnt money. “I wanted to create a B2B vertical and people wanted to write about Ferraris and Hayabusa’s,” he says.

So after the dotcom bust, it was back to B2B again. But Agarwal is proud of one of his websites from the clutch he still maintains. Biztradeshows is the world’s leading site on trade fairs. “When Google has to look for some trade show info, they look at us,” he says.

For any business, it’s very important that the distance between CEO and the frontline is minimum. That means keeping your ears to the ground. Hands-on CEO that he is, Agarwal often picks up the phone and calls the buyers and suppliers or even his own branch to check what’s going on. Even at trade fairs, he is at his stall meeting prospectives. And if his old customers sometimes call him to complain about things not working, he personally looks in to the matter. “It’s important to remain in touch. A trunk means box and also an underwear. So it’s important to understand the needs of a buyer and seller and listen to what they are trying to convey,” he says.

Sites like Snapdeal and Justdial also cater to some parts of the SME market, but competition doesn’t bother Agarwal. His audience is largely between Rs 50 lakh to Rs 50 crore, and within it, the bulk is between Rs 2 crore and 20 crore. “The Groupon SMEs are different, even the Justdial SMEs are different. New economy, old economy, manufacturing, service, have different mindsets. There is let than 2% overlap between SMES that I cater to and what my competition does,” he says.

Ask him what next, and pat comes the reply: “Today, 20% of all buying and selling is happening within my community. I feel that it can go as high as 50%,” he smiles. So it’s basically back to dhanda.